Making sure your blood sugar stays at normal levels is the most important technique in managing diabetes. For those of us relying on insulin, we don’t just have to worry about highs, but also worry (maybe even more-so) about lows. Typically, blood sugar will go low due to exercise or excess insulin, and it can happen fairly frequently if we don’t have our basal/bolus correct. But when do we say a blood sugar is “low” anyway? What’s the best way to correct it when it is? And what kind of food is ideal for correcting it?

What is a “low” blood sugar?

Let me first note that I’ll be speaking in terms of mg/dl. If you use a different unit of measurement, feel free to reference this chart. A healthy individual’s fasting blood sugar (as in, not right after eating some cake) is around 80-90. That being the case, most experts would consider 80-90 to be a great blood sugar, and below 70 to be getting into “low” territory. Some would recommend correcting blood sugars as high as 100, but I believe this comes out of a fear of diabetics being so out of control that even near-low numbers are a threat. If you’re following the principles laid out by Dr. Bernstein, this shouldn’t be a concern, and you need not consider anything above 70 to be low. After all, if normal blood sugars are what we’re after, we shouldn’t correct a normal blood sugar. I personally will only correct if it’s below 70.

That said, context is key. For example, if you have lots of insulin on board and you know it’s effect hasn’t finished yet, 70 could mean 60 or even 50 later, and it may be a good idea to be safe and correct a bit for it. This can especially be a danger if you’re about to go to bed. You also need to be cautious if you’re sick or haven’t figured your basal rates out. In such cases, it’s sometimes better to be safe than sorry. Unless you know your blood sugars will stay level and aren’t dropping, it may be good to exercise some caution.

What’s the best way to manage a low blood sugar?

Typical guidelines would suggest correcting for a low, any low, with 15g of carbohydrate. I find this dubious and prone to error, especially if you’re eating low-carb and suddenly less tolerant to sugar. Your goal should always be getting back to normal blood sugars, rather than just getting out of a low. Blindly flinging the same amount of sugar at a 65 that you would at a 35 will leave you way higher than you want, followed by an insulin dose that might bring you back low again. You don’t want to be up and down constantly. How do we avoid this roller coaster? Through testing and establishing predictability.

What do I mean by that? I mean finding out exactly how many grams of sugar raise your blood sugar by how many points, and using that to judge how much sugar you need to get back up to that magic 80-90 range. That means taking more sugar if you’re very low, and less if you’re just on the edge. That means knowing exactly how much sugar you need to get from 50 to 80 and no further, and eating just that much rather than 15 grams every time. How do you do that, and where do you start?

Dr. Bernstein notes that, for the average person, 8 grams or sugar will bring blood sugar up by 40 points. Use this as your starting point. When you have a low, let’s say it’s 50, take those 8 grams of sugar. Half an hour later, test your blood sugar and see where it’s at. If it’s still low, you know you need to take more. If it’s at 120, you know you need to take less. Simple, right? Write all of this down; your low blood sugar, how much you took, and the result. Keep doing that experiment, tinkering with it every time you’re low, until you’re able to figure out your exact sensitivity to glucose, and thus able to predict how much sugar you need to get back to that golden range consistently.

What should you correct with?

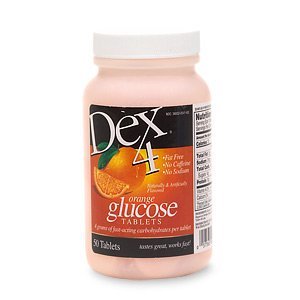

When you do this experiment, you don’t want any confounding variables. This is why it’s important that you always correct with something that is consistent, like glucose tabs. Not candy, not chips, not a box of cookies. Why? Because only glucose tabs are specifically made to be precise, while typical sweets are not. And, those sweets come with various ingredients that might impact how your body absorbs them. 8g of sugar from grape juice or a Twix may impact you differently than 8g from pure sugar. You want to have as little variables as possible, so stick to correcting with glucose tabs. That way, you know exactly what you’re getting and it’s more predictable.

Another benefit to glucose tabs is that they are less tempting. After all, they taste like chalk. Especially the grape ones, YUCK! That’s actually a good thing. Being low shouldn’t be a rewarding experience that gives you an excuse to eat the cheat foods you miss the most. Especially if you’re raising a t1 child, giving them a treat every time they’re low is asking for trouble. Plus, you risk falling back into bad habits by enjoying the treats you’re now abstaining from. Avoid that risk and avoid creating rewards for missteps by sticking to something simple and not-very-pleasant, such as glucose tabs. For a cheaper alternative, you can use smarties, though they are more tempting

Key Take-Aways:

- Correct when you’re under 70 mg/dl in most cases.

- Experiment and test to find exactly how much sugar you need, and don’t over-do it.

- Use glucose tabs to keep things predictable and not tempting.